Introduction

If we pray to Kwan Seum Bosal to remove our “karmic obstructions” (as discussed in the previous section), well, what if it actually works? Once these karmic obstructions are removed, or at least reduced, what is it that we are now able to do. That is, what was, but now is not, being obstructed? What is our aspiration?

The Korean Zen Master Seung Sahn had a little formula that he used to express the aspiration of a Bodhisattva: “get enlightenment and save all beings”. In the book “Only Don’t Know“, which is only 250 pages long, Master Seung Sahn uses this phrase at least 30 times. For a Bodhisattva this is really the only aspiration that matters.

In fact, this is the very definition of what it means to be a Bodhisattva. Often we emphasize the “save all beings” part. But how do I save all beings? Only a Buddha could possibly do that. By definition, to be a Boddhisattva is to vow to become a Buddha. Not for the sake of ending one’s own suffering, but because only a Buddha can truly save others from the suffering of Samsara.

To summarize where we are now in the chant: (1) First we take refuge in the Triple Gem, then, (2) we recite the name of “Kwan Seum Bosal”, then, (3) we recite Kwan Seum Bosal’s mantra to help us get rid of karmic obstructions, and now, (4) we recite the mantra for accomplishing our great aspiration as Bodhisattvas.

Mantra Title: “The Mantra of the Accomplishment of Great Aspirations”

The intention to “get enlightenment and save all beings” is certainly a “great aspiration”. This is reflected in the title of our next mantra: “The Mantra of the Accomplishment of Great Aspirations” (大願成就眞言). Note that in practice, the title is often shortened by leaving off the first character (大). Here is the Hanja, pinyin, Hangul, romanized transliteration, and literal English translation, of the title:

大 願 成 就 眞 言 (Hanja)

(dà) yuàn chéng jiù zhēnyán (pinyin)

(대) 원 성 취 진 언 (Hangul)

(dae) won seong chwi jinon (romanized)

(great) aspiration succeed accomplish true words (translation)

Some notes on the Hanja:

大 is a very common character, especially in a Buddhist context. Buddhists always want everything to be “great”. However, there is more than one way to say “great” in Chinese (see below).

願 is also featured prominently in the Four Great Vows, where the two character combination 誓願 is translated to English as just “vow”, although the first character, 誓, by itself already means “vow”, or “aspiration”. Also in the “Four Great Vows” it’s interesting to note that it is the character 弘 that is being translated as “great”. You might also recognize the character 弘 from the first post on Kwan Seum Bosal Chanting.

成就 is a two character combination that means “achieve” or “success” or “achievement”.

Although in practice it is literally left unspoken, it’s good to remember that first character of the title, 大. That character is there to remind us of our “great” aspiration, the aspiration of a Bodhisattva. Of course, we also have lots of other, less exalted, aspirations. And in this context it’s important to know that the character 願 can also be translated as “wish” or “desire”. As discussed further below, this is actually an extremely popular mantra in Korea, and it is very often viewed as a general purpose “wish-fulfilling” magic charm. But when the mantra is done as part of Kwan Seum Bosal chanting, it is clearly directed to that highest of all aspirations: “get enlightenment and save all beings”.

The Mantra: 唵 阿暮伽 薩婆怛囉 傞陀耶 始廢 吽

Here are the Hanja, pinyin, Hangul, and romanized transliteration of the mantra:

唵 阿暮伽 薩婆怛囉 傞陀耶 始廢 吽

ǎn āmùqié sàpódáluō suōtuóyé shǐfèi óu

옴 아모카 살바다라 사다야 시베 훔

om amoga salbadara sadaya shibye hum

I have not been able to find any indication that this mantra is currently in use outside of Korea. As to the original Sanskrit, well, the first and last syllables (om: ॐ and hum: हूँ) are straightforward enough. Also, “amoga” is quite possibly अमोघ, “unfailing”. And “sadaya” could very well be सदया, “compassionate”. The other two parts, “salbadara” and “shibye” are still a mystery, Sanskrit-wise, at least to me.

But perhaps a little more could be said about that last syllable: hum. Just as there are many mantras that begin with ॐ (om) and end with स्वाहा (svaha), there are also some very interesting mantras that start with ॐ (om) and end with with हूँ (hum). In particular, there is the famous six-syllable mantra of Kwan Seum Bosal: om mani padme hum. Kukai wrote that hum “encompasses the truth taught in all the Buddhist sutras and sastras.” Kukai goes on further to assert that just as all the teachings are subsumed by the three phrases “bodhicitta is the cause, universal compassion is the root, and skillful means is the goal”, these three phrases, in turn, are all subsumed in the single syllable “hum”. (From his Unji gi, “The Meanings of the Letter Hūṃ”). Also, in the “Mantra of Purification”, “om ah hum” (嗡阿吽), the syllable “hum” is the seed syllable for the mind (while “om” is the body, and “ah” is speech).

But perhaps a little more could be said about that last syllable: hum. Just as there are many mantras that begin with ॐ (om) and end with स्वाहा (svaha), there are also some very interesting mantras that start with ॐ (om) and end with with हूँ (hum). In particular, there is the famous six-syllable mantra of Kwan Seum Bosal: om mani padme hum. Kukai wrote that hum “encompasses the truth taught in all the Buddhist sutras and sastras.” Kukai goes on further to assert that just as all the teachings are subsumed by the three phrases “bodhicitta is the cause, universal compassion is the root, and skillful means is the goal”, these three phrases, in turn, are all subsumed in the single syllable “hum”. (From his Unji gi, “The Meanings of the Letter Hūṃ”). Also, in the “Mantra of Purification”, “om ah hum” (嗡阿吽), the syllable “hum” is the seed syllable for the mind (while “om” is the body, and “ah” is speech).

As is the case with “svaha” (and even with “om”!), there are many different ways to pronounce (and write) “hum”. The Chinese character is 吽, which is usually pronounced something like “hum”, although the pinyin is often given as “óu”. In Tibetan it is ཧཱུྃ (also see the image to left), and is pronounced “hung”. The Korean Hangul is 훔, pronounced “hum”. In Sanskrit it is हूँ, pronounced hūṃ. The beautiful “Om Ah Hung” sticker pictured above and to the left is available for purchase from the good people at TibetanTreasures.com on their website – here is the direct link to it.

Wish Fulfillment

Below is a fascinating excerpt from “Dharani and mantra in contemporary Korean Buddhism: A textual ethnography of spell materials for popular consumption”, a 2019 article by Richard D. McBride, published in the Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 42 pp. 361–403:

Buddhist supply shops and stores located near the premises of Buddhist temples sell a wide assortment of objects that may be considered talismanic. Talismans come in a wide variety of forms. For instance, talismans and charms can be small rosary-bracelets, necklaces showcasing a small Buddha image, key chains, small wooden tablets, and small gold-colored cards (5 cm by 8 cm) in protective plastic cases featuring Avalokiteśvara and Bodhidharma. Many of these have the expression “realization of one’s desires” (sŏwŏn sŏngch’wi) carved or impressed in either Sinitic logographs or the Korean script on individual beads of the rosaries. One popular and inexpensive talisman of the gold-card type is an attractive feminine-looking white-robed Avalokiteśvara bearing a kuṇḍikā in her right hand, and standing on a red lotus blossom. The talisman has the “mantra for realizing one’s desires” (sŏwŏn sŏngch’wi chinŏn 誓願成就眞言) written in the Korean script along with the words of the spell: “Om amok’a salbadara sadaya sibe hom” (옴 아모카살바다라 사다야시베홈). The shape of the talisman makes it easy to carry on one’s person in one’s wallet or purse.

The talisman described above has written on it the very mantra that we are here discussing, complete with title, although note that the title differs in the first character: 誓, instead of 大. That slight difference in the title doesn’t really appear to be that significant of a deviation, since “誓願” is the same two character combination found in “The Four Great Vows” (see the earlier post on that subject).

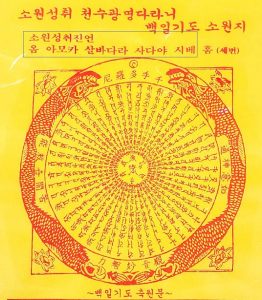

To the right is an image of an amulet that one can purchase online, similar to the ones described by McBride above. On the amulet one can see, in Hangul, both the title (소원성취 진언) and the mantra itself (옴 아모카 살바다라 사다야시 베홈). Since there is also a lot of other writing on the amulet, I have added a thin blue rectangle to help make it easier to see exactly where the mantra and the title, above it, are located (click on the image to see a larger version). Note that this “lucky” talisman uses the same title as the one described by McBride in his article. The description, in Korean, of this amulet is “[부적]소원성취천수광명다라니“, which translates to something like “[Amulet (부적)] Wish Fulfillment, Thousands (천) of Lights, Gwangmyeong (광명), Dharani (다라니)”. It’s currently on sale for 1,000 won. Here’s a direct link to that specific item, and here’s a link to the page I found it on, where there are many more similar items for sale. (I have no knowledge concerning this vendor, and I have never purchased anything from them.)

To the right is an image of an amulet that one can purchase online, similar to the ones described by McBride above. On the amulet one can see, in Hangul, both the title (소원성취 진언) and the mantra itself (옴 아모카 살바다라 사다야시 베홈). Since there is also a lot of other writing on the amulet, I have added a thin blue rectangle to help make it easier to see exactly where the mantra and the title, above it, are located (click on the image to see a larger version). Note that this “lucky” talisman uses the same title as the one described by McBride in his article. The description, in Korean, of this amulet is “[부적]소원성취천수광명다라니“, which translates to something like “[Amulet (부적)] Wish Fulfillment, Thousands (천) of Lights, Gwangmyeong (광명), Dharani (다라니)”. It’s currently on sale for 1,000 won. Here’s a direct link to that specific item, and here’s a link to the page I found it on, where there are many more similar items for sale. (I have no knowledge concerning this vendor, and I have never purchased anything from them.)

All of this talk about magical amulets and talismans is a good reminder of the very broad range of meanings and usages for mantras and dharanis among Buddhists (and, for that matter, non-Buddhists). These meanings and usages are not at all neatly separated from each other. This should not come as a surprise, nor should it appear to be in any way “un-Buddhist”, so long as one has at least some familiarity with the Lotus Sutra. In Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra it clearly states that Kwan Seum Bosal has “supernatural powers” and “can confer many benefits”. Among the many mundane perils and misfortune that Kwan Seum Bosal is purported, in the Lotus Sutra, to be able to deliver us from, are “weariness”, bad weather (“lightning … hail … and drenching rain”), legal problems (up to and including being condemned to execution), “lizards, snakes, vipers, and scorpions”, and so forth. (Link to English translation of this chapter)

Sources / Resources

Three different renditions of the mantra being chanted by Korean Buddhists:

• https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfarVPNgLps

• https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Re4tl8MrnyA

• https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_nBewxcfypo

More on the syllable “hum”

• A very interesting article on “The seed syllable hūṃ” at the visiblemantra website: http://www.visiblemantra.org/hum.html

• Often one finds explanations of “hum” embedded in broader teachings on “om mani padme hum”, as in this video of a teaching by the Dalai Lama: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4QQKDP8SQZg

• Another mantra that ends with “hum” is the “Purification Mantra”, “om ah hum”. Here is a teaching on that mantra: https://www.lamayeshe.com/article/om-ah-hum-meditation

Buddhism, Magic, and Wish Fulfillment

There is a popular little booklet for sale in Korea entitled, simply, “Let’s Achieve Buddhahood”, by Ven Chagwang (滋曠). In his article on “Dharani and Mantra in Contemporary Korean Buddhism” (referenced above), Richard McBride provides the following translation from the section of that book on the subject of “Spell Power”:

Spell power (churyŏk 呪力) refers to the majestic power of mantras (chinŏn 眞言; lit. “true words”) and dhāraṇīs (tarani 多羅尼). Mantras are the true words of the Buddha. Dhāraṇī is translated as meaning “comprehensively grasp [or to hold or maintain comprehensively]” (ch’ongji 總持). With respect to dhāraṇīs, one letter or one phrase contains many meanings. There is great vitality for miraculous transformation in the true words of the Buddha. Therefore, if you recite true words you will eliminate calamities, achieve auspicious omens, extinguish karmic hindrances, and be reborn in the world system of Extreme Bliss. If you recite mantras you will receive the submission of hosts of demons, be cleansed of filthiness, be possessing of surpassing [susŭng 殊勝] courage and wisdom, obtain limitless power, and achieve limitless merit.

When you recite these mantras first cleanse your body and mind and behave decently. If you make your mind like Mount Tai and recite mantras with utmost sincerity, just as a shout in a great mountain gorge becomes an echo, you will obtain a bestowal of protective power [kap’iryŏk 加被力] from all the buddhas and bodhisattvas and your courage and wisdom will be increased [chŭngjang 增長].

Also, when you recite mantras, you will obtain something of personal power. Your own body and mind will be unified and to the extent that they become clean and pure all hindrances within your own psyche [chŏngsin 精神] will disappear. Therefore, you will produce the conviction, wisdom, and courage to be able to work out whatever goal or purpose you desire by means of spell power. We will be able to say that we can go to the Buddha-stage [pulchi 佛地] through this spell power.