• Make your own practice sheets: Make your own character practice sheets at chineseconverter.com Make your own character practice sheets at purpleculture.net • You can also just buy books of ready made blank practice sheets. Personally I recommend “Mi-Zi-Ge” style with big squares, like this one available at Amazon: • Tuttle’s flashcards are really nice. […]

Category: chinese

Four Great Vows: practice using Tuttle’s “First 100 Chinese Characters” and “Second 100 Chinese Characters”

• Lesson One: Most of the characters in Lesson One (derived from the title of the Four Great Vows) do not have their own entries in Tuttle’s “First 100 Chinese Characters” or “Second 100 Chinese Characters“. However, all but four have relevant entries that can be useful for practice. All page numbers below are in […]

Four Great Vows online class Master Page

One page to rule them all

This is a “master” page/post that should contain links to everything in this blog related to the online course: “The Four Vows in Chinese Characters”.

Video for First Lesson of Four Great Vows online class

Here is a link to the full 2 hour video of the first Four Great Vows class: If you have any feedback or want to ask a question please leave a comment to this post.

Zhiyi, the Lotus Sutra, and the Four Great Vows

Here are links to three relevant relevant articles, with excerpts. Outline of the Tiantai Fourfold Teachings 天台四教儀 Compiled by the Goryeo Śramaṇa Chegwan 高麗沙門諦觀, Translated by A. Charles Muller 一未度者令度。卽衆生無邊誓願度。此緣苦諦境。 All those who have not yet been saved will be saved, which is expressed as “I vow to save all living beings without limit.” This […]

Confucius says: “No pain, no gain” (Analects 7:8)

[7-8] 子曰。不憤不啓、不悱不發。擧一隅不以三隅反、則不復也。

[7:8] The Master said: “If a student is not eager, I won’t teach him; if he is not struggling with the truth, I won’t reveal it to him. If I lift up one corner and he can’t come back with the other three, I won’t do it again.”

Four Great Vows: Lesson Two

Lesson Two

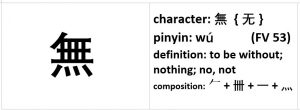

四 弘 誓 願

眾 生 無 邊 誓 願 度

煩 惱 無 盡 誓 願 斷

法 門 無 量 誓 願 學

佛 道 無 上 誓 願 成

“I am bothered when I do not know others.” (Analects 1:16)

子曰。不患人之不己知、患不知人也。

Charles Muller’s translation:

[1:16] The Master said: “I am not bothered by the fact that I am unknown. I am bothered when I do not know others.”

Confucius asks about everything. (Analects 3:15)

子入大廟、每事問。或曰。孰謂鄒人之子知禮乎。入大廟、每事問。子聞之、曰。是禮也。

When Confucius entered the Grand Temple, he asked about everything.

Someone said, “Who said Confucius is a master of ritual?

He enters the Grand Temple and asks about everything!”

Confucius, hearing this, said, “This is the ritual.”

[Analects, 3:15]