In dealing with East Asian Buddhism, Japanese and Westem scholars are

easily exposed to Japanese Buddhist sectarianism and western Christian sectarianism.

However, from the introduction of Buddhism to the period of Wonhyo, there are no

institutionalized sects that resemble Western religious sects or Japanese Buddhist sects.

For example, the scholars of the Chinese Huayan sect, actually established by Fazang,

do not have strong sectarianism, compared to Japanese Buddhist sectarianism and

western Christian sectarianism. The “Huayan sect” refers simply to the group of

scholars who are interested in Huayan Buddhism.

Category: buddhism

Four Great Vows in Hanja, Hangul, and romanized transliteration

衆 生 無 邊 誓 願 度

중 생 무 변 서 원 도

jung saeng mu byeon seo weon do

everything born without limit vow to liberate

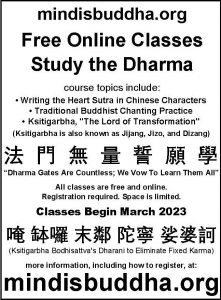

Traditional Buddhist Chanting

Over a twelve month period, starting in March 2023, this course will cover the following six chants (we will spend two months on each chant):

Yebul / Homage to the Three Jewels

Kanzeon

Heart Sutra

Great Dharani

Kwan Seum Bosal / Jijang Bosal

Master Uisang’s Song of Dharma Nature

The Jijang Bosal Book Club

The is the “Master” page for everything related to the “Jijang Bosal Book Club”. This reading/discussion group will meet twice a month on the second and fourth Tuesdays, starting at 7pm on March 14.

We will be reading and discussing four books related to Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, known as Jijang Bosal to Korean Buddhists (and as Jizo in Japan and Dizang to Mandarin speakers).

Charles Muller on interpenetration (通達) and essence-function (體用)

Exclusive reliance on Western modes of interpretation need not in itself be harmful. But it appears as if it can be, as we can see a distinct tendency in recent works on East Asian religion, and especially East Asian Buddhism, to regard the object of study in a disparaging manner. To, for example, wrap up the texts of the entire East Asian Ch’an/Sŏn/Zen traditions as being little other than rhetorical devices, or to report on the East Asian religious traditions by concentrating on examples of how poor East Asian Buddhists supposedly were at grasping the implications of their own writings. Or, on the other hand, to suggest that now that ten percent or so of the East Asian canon has been rendered into English, it is time to stop expending our energies in the effort of translation and interpretation, and rather devote ourselves toward the investigation of living traditions. Over its first century of existence, Western scholarship on the East Asian religions has tended toward two extremes: naive acceptance (seen during earlier periods of scholarship) or a subtle, but nonetheless perceptible arrogant downlooking, in which the leading figures of the tradition are seen as being wholly preoccupied with sectarian motivations, and either hopelessly simple-minded or untrustably deceptive.

How to use the “Writing the Ox” web application

The “Writing the Ox” web application is designed to help English speaking Buddhists learn Traditional Chinese Characters. A lot of the application is (hopefully) intuitive. Basically you can just go directly to it and start clicking around and see what happens. But it might be helpful to have some of the basics of the application explained for those using it for the first time.

More resources for studying The Four Great Vows

• Make your own practice sheets: Make your own character practice sheets at chineseconverter.com Make your own character practice sheets at purpleculture.net • You can also just buy books of ready made blank practice sheets. Personally I recommend “Mi-Zi-Ge” style with big squares, like this one available at Amazon: • Tuttle’s flashcards are really nice. […]

Four Great Vows: practice using Tuttle’s “First 100 Chinese Characters” and “Second 100 Chinese Characters”

• Lesson One: Most of the characters in Lesson One (derived from the title of the Four Great Vows) do not have their own entries in Tuttle’s “First 100 Chinese Characters” or “Second 100 Chinese Characters“. However, all but four have relevant entries that can be useful for practice. All page numbers below are in […]

Four Great Vows online class Master Page

One page to rule them all

This is a “master” page/post that should contain links to everything in this blog related to the online course: “The Four Vows in Chinese Characters”.